Without a doubt Çatalhöyük is the most well-known and important archaeological site in the world. James Mellaart was behind the discovery that took place in the 1960’s, while for more than 20 years now this site has been associated with one of the most significant archaeological personalities - Ian Hodder. Thanks to the exceptionally favourable natural conditions a large number of movable and immovable monuments have been preserved, covering the entire varied gamut of artistic expression, which for a long period had no other comparable analogy.

|

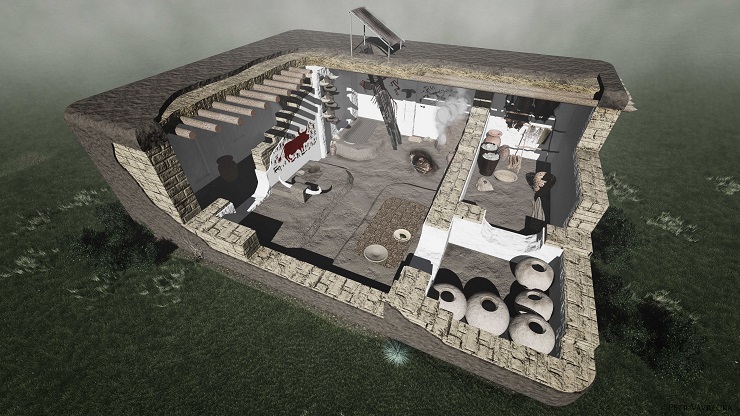

| The Çatalhöyük settlement is noteworthy for its typical dense development in the old Turkish style. As is evident from this loose reconstruction, movement between the residential units was possible only over the rooftops. A considerable portion of the regular day-to-day activities also took place on the roofs. The cross-sections offer a view of the internal layout of the houses. Author Petr Vavrečka. |

These actually represent two settlement mounds of different heights and sizes, known as tellas, that are separated by a depression with watercourse. The eastern mound covers an area of 13.5 hectares and reaches a height of 21 m. Inside it there are findings from a hidden settlement of the Pre-Pottery period, while the major discoveries, however, fall within the Ceramic Neolithic period. Not counting the Byzantine and the Muslim tombs, the topmost preserved layers are associated with the beginnings of the more intensive expansion of the production of copper artefacts that took place during the 6th millennium BC. The western knoll covers an area of cca. 8 hectares and a settlement was already flourishing there at the beginning of the 6th millennium BC.

|

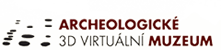

| This loose reconstruction of a multi-space house shows the main room together with its roof entrance, its heating equipment and its ritual space. Often, located beneath the floor, there are the burial places of individuals of different sexes. It is interesting that these persons do not necessarily have to be related by blood. Author Petr Vavrečka. |

All the building units were constructed from adobe bricks. In the eastern area 18 major construction phases were documented comprising incredibly dense originally squared buildings. All the movement around the settlement took place across the roofs of the houses, while from the roofs the main entrances were reached by means of ladders. Based on recent research, the houses were apparently arranged in larger sectors, comprising between ten and fifty buildings and probably also into smaller agglomerations of between three and ten buildings located around the main common building, which, by today’s scholars, is referred to as the “house with memory”. The arrangements of these small groups have both economic and social connotations that are now gradually being deciphered. In the direct vicinity of these houses there were also small courtyards containing thick layers of refuse emanating from the interiors of houses in which various everyday activities took place.

The documentation of the activities that took place inside the house has been preserved, specifically because of the practices that were associated with its abandonment. The artistic manifestations on the walls, the furnaces and the other interior equipment were all covered beneath thoroughly sorted soil. The lifetime of the houses, however, probably not based on practical reasons, was estimated as being between 50 and 100 years. After the functioning of the house terminated the upper parts of the walls were destroyed, while the remaining lower parts served as the foundation for a new building – in the same place and with the same dimensions. There is evidence of four to six reconstructions all taking place at one single location.

Also of interest are the spaces beneath the floor, considered as providing evidence of the links existing between the world of the living and the world of the dead. The dead were buried beneath the floors of houses without any distinction being made between either their age or their gender. Overall, based on how they were treated, it is possible to assume that they had an important role in the life of their local communities.

The western hill differs in certain aspects. The houses, which also comprise more rooms, are arranged in a different manner. No burials beneath the floors of buildings were documented in that location. The skeletal remains of animals provide obvious evidence of their domestication. The termination of the Çatalhöyük settlement is currently a subject of research and it is probably connected with changes that have been documented throughout the Near East.

|

|

| The manner of research of the Neolithic sites located in the Near East looks quite different than it does in Europe. Remains of buildings that were repeatedly rebuilt at one location are visible in this profile, representing a remnant of Mellaart’s exploration of the eastern hill. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2005. |

Want to learn more?

- Biehl, P. F. 2012: Rapid Change versus Long-Term Social Change during the Neolithic-Chalcolithic Transition in Central Anatolia. Interdisciplinaria Archaeologica natural Sciences in Archaeology III/1, 75-83.

- Hodder, I. 1999: Renewed work at Çatalhöyük. In: Özdoğan, M. – Başgelen, N. 1999: Neolithic in Turkey, the Cradle of Civilisation. Istanbul: Archaeology & Art Publications, 157-164; Hodder, I. 2011: Çatalhöyük: A Prehistoric Settlement on the Konya Plain. In: S. R. Steadman – G. McMahon (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of ancient Anatolia. Oxford: Oxford University press, 934-947.

- Hodder, I. 2011. Çatalhöyük : the leopard’s tale : revealing the mysteries of Turkey’s ancient "town". London: Thames and Hudson.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)