Distribution, gift giving and exchanging constitute a big issue for archaic societies. In the Western world the natural monetary economy is based on the principle of achieving a material profit during every transaction. That does not mean, however, that it is applicable in all cultures that in an exchange trade both sides must obtain the same economic benefit. In the 1950’s the economic historian Karl Polanyi developed a system for classifying the different modes of the distribution of commodities. He identified three different types: reciprocity, redistribution and trade exchange. Both redistribution and the existence of market are subject to the activities of the central power organisations and therefore these categories are typical of those societies with advanced power and economic hierarchies. More interesting for us therefore will be the reciprocal relationships in archaic societies.

|

|

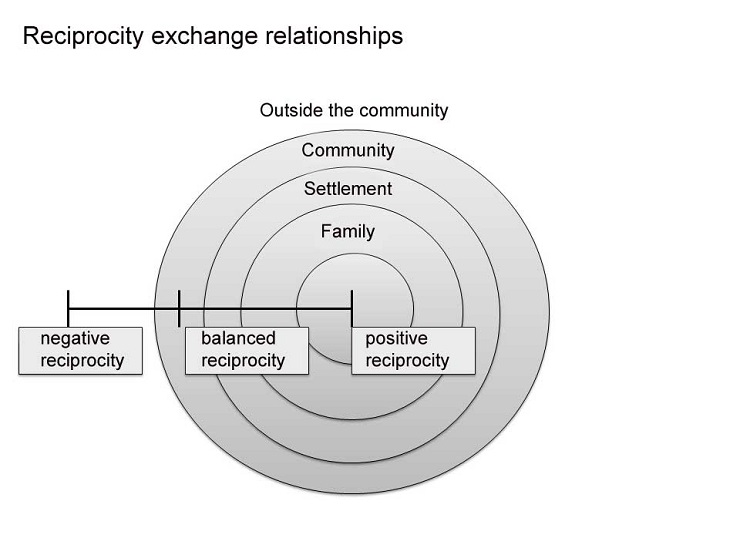

The layout of reciprocal exchange relations in regard to the diverse planes of social integration. |

Reciprocity refers to transactions between two parties in which there is a transfer of assets and of services. The participants in the exchange basically have a symmetrical social relationship, which means that they can be equal exchange partners. The exact category of reciprocal transactions can be broken down in greater detail – i.e. positive or general reciprocity, balanced reciprocity and negative reciprocity. What determines the specifics of a reciprocal relationship is any difference in the value equivalence of the commodities that are exchanged. In classic pre-monetary trade exchanges it was only possible to exchange one item for another that had a corresponding value. This rule, however, is not applicable in regard to a positive reciprocal relationship, because it is closer to our concept of a gift than to a trade.

The basis of the anthropological theory of gifts was established by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss. He discovered that in many societies, especially those that lack a monetary economy, the links of social relationships are strengthened by a sequence of exchanges of gifts. This is the gesture that defines the commitment of the two parties in exchange for the strong social pressure, especially on the side of the recipient of the gift. The latter is expected to quickly repay his or her commitment with a gift of a similar value. These mutual and reciprocal services take place formally, by and large on a voluntary basis and they always involve gifts and donations, however they are strictly required, essentially under the threat of private hostility or of complete social elimination. Donations can also be used to offset the potential risks of economic failure and also for the consolidation of social relations within the community. This reciprocity also serves to eliminate proprietary differences in the society, the power-organisational nature of which is based on egalitarian principles.

|

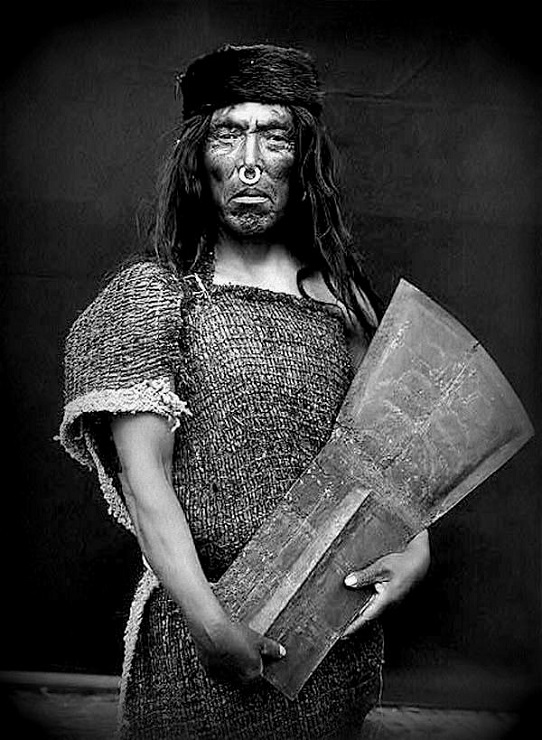

| The man belonging to the indigenous Kwakwakawakw group is holding a copper shield-shaped object. Photo by Edward S. Curtis (adjusted). Wikimedia Commons. |

A third type of bilateral exchange relationship is negative reciprocity. The basic principle of this is that we seek to obtain the maximum return for donated or exchanged articles. In other words, we do expect a profit. Negative reciprocity can occur between individuals who are socially distant or even between strangers; this is logical, because a successful transaction for one side is usually disadvantageous for the other side.

The Kula exchange system

Bronislaw Malinowski, who conducted research on the Trobriand Islands in the western Pacific, managed to penetrate the basic principles of the local natives economic and social system – basically meaning the exchange of gifts. The participants in this specific type of ceremonial exchange were travelling hundreds of kilometres in canoes to all the neighbouring islands, carrying with them red clam necklaces (to the north counter-clockwise), and also bracelets made of white shells (to the south clockwise). This system involved several thousand people and a total of eighteen island communities. The natives named this entire special exchange system kula. Ornaments in the form of necklaces or bracelets represented the highest exchange category; they were also preceded by other gifts, however. What was of major importance to them in regard to the ornaments was raising the profile of their owner, who was temporary, because all the commodities circulated throughout the kula ring.

The Moka exchange system

The moka exchange system was (and it probably still is, in some form) a highly ritualised exchange system prevalent in the Mount Hagen area in the Highlands of New Guinea. It is based on the reciprocal exchange of pigs, by means of which an individual’s social status is identified. What is crucial is to give more pigs than you receive, which is how personal prestige is obtained and thereby it is clear that the individual excels in the society. Other potential gifts are rare sea shells that are obtained on the coast through exchanges. The received gift creates an obligation, the actual profit from which is the social success of the donor. The recipients should not only strive to settle their “debts” rapidly but also to transfer them to the primary donor. This is achieved simply by returning more than you had obtained. At its highest level this moka system became a platform for competition between a limited number of men who enjoyed the benefits of having a high social status. From this foundation the exchange system expanded to include many hundreds of other men, all vying with each other for both prestige and social recognition.

|

|

|

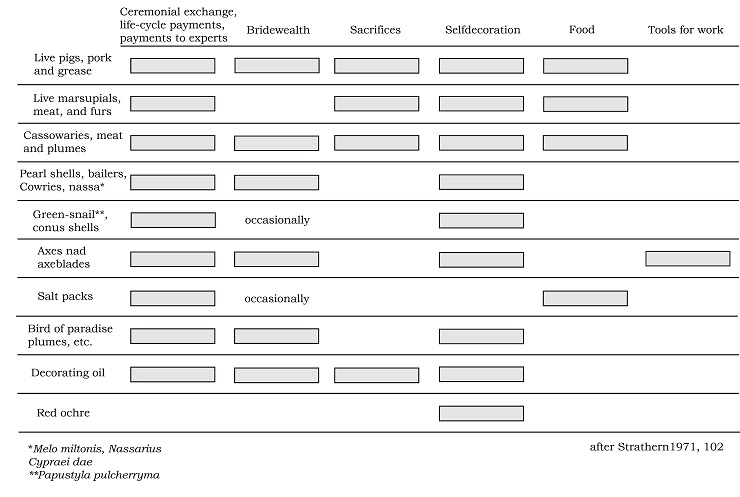

Moka exchange did not represent the only opportunity in the Highlands of New Guinea for the exchanging of commodities and for gift giving. The adjacent diagram shows the various kinds of exchange activities and also the commodities that were traded in the course of them. |

Potlatch

The potlatch was a different manner of the mass distribution of commodities that was practiced by all the cultural groups on the northwest coast of North America. It represented a very typical ceremony in this area. Each person who was born there had a certain status that included specific rights, but these were not confirmed or recognised until the potlatch ceremony had taken place. This concerned, for example, being given a name or being granted the right to use an ancestral mythological “coat of arms”. The potlatch simply helped to define the individual’s place in the society. If any group decided to hold a potlatch, it was required to first accumulate a large amount of property, because the distribution of that property was actually the main point of the upcoming ceremony. The organising group invited members of neighbouring or distant communities to the ceremony, who then served as witnesses to the acts that were confirmed by the potlatch. All the names, privileges and “coats of arms” awarded were supported by the testimony of the participants, whose loyalty was secured by the plentiful gifts that they received as members of the hosting group. The potlatch thereby helped to support social relationships within the individual communities, while, at the same time, it also created both personal and political ties between diverse groups. Both the ordinary members of the hosting groups who thereby identified their societal position and also showed off both their titles and their rights and also the chieftain, who was the official donor of all the commodities that were exchanged and thereby the most important person, were all actively involved in the ceremony.

|

|

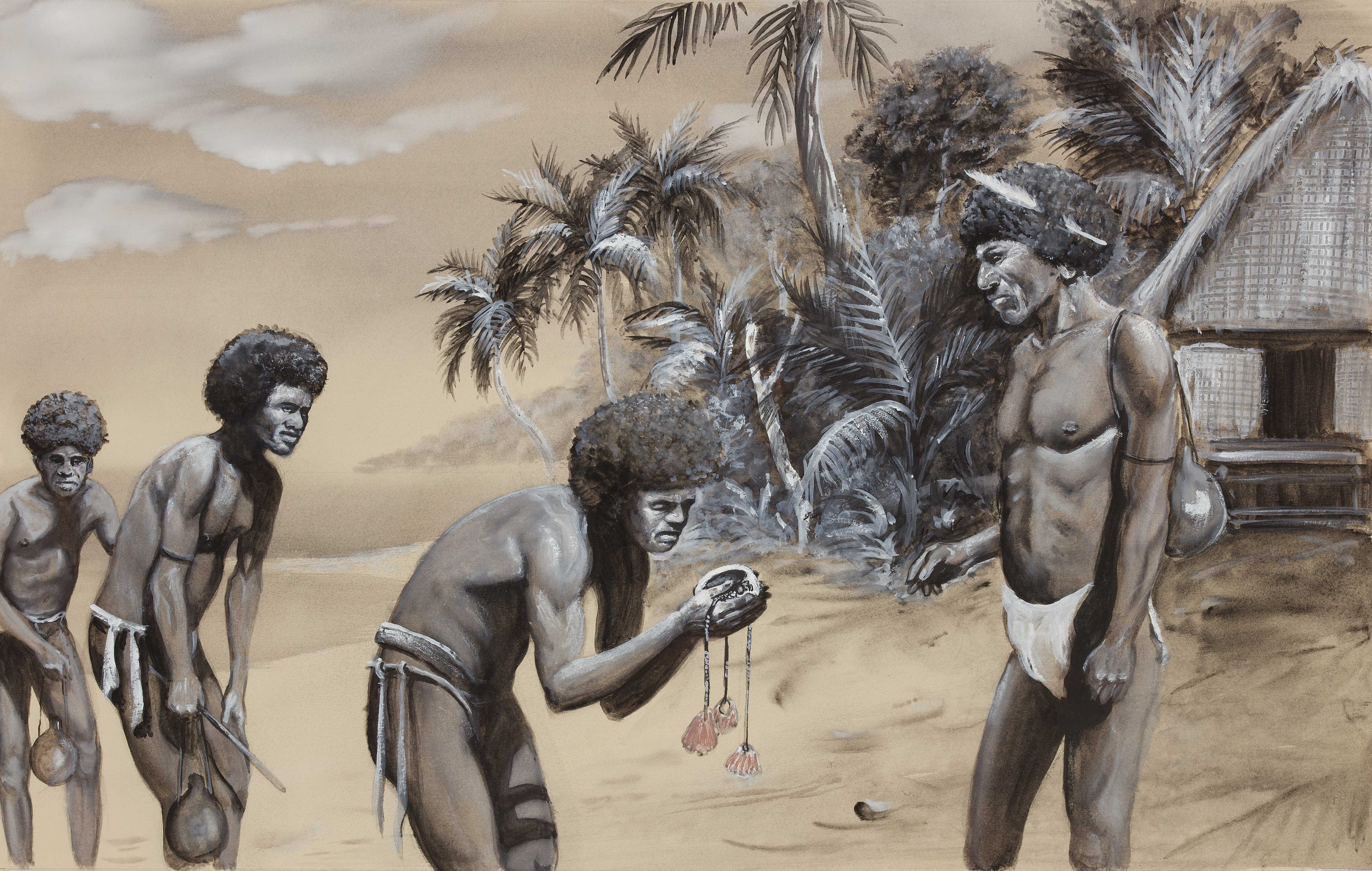

| The kula exchange system, in place on the Trobriand Islands in the Pacific, represents a textbook example of a business concept that is not based on market principles. What this means is that the exchanges are not motivated by the anticipation of an immediate material gain, but rather by social prestige. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

Want to learn more?

- Damon, F. H. 1980. The Kula and Generalised Exchange: Considering Some Unconsidered Aspects of the Elementary Structures of Kinship. Man, New Series 15 (2):267-292.

- Drucker, P. 1955. Indians of the Northwest Coast. New York: The Natural History Press.

- Godelier, M. 1999. The Enigma of the Gift. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press and Polity Press in Association with Blackwell Publishers, Ltd.

- Malinowski, B. 1920. Kula: the Circulating Exchange of Valuables in the Archipelagoes of Eastern New Guinea. Man 20:97-105.

- Malinowski, B. 1922. Argonauts of the western Pacific. New York: Dutton.

- Mauss, M. 1925: The Gift. London: Routledge.

- Nairn, Ch. 1980. Ongka’s Big Moka. Movie. 59 minute: Documentary Educational Resources.

- Polanyi, K. 1957. The economy as instituted process. In Trade and Market in the Early Empires, eds. K. Polanyi, M. Arensberg, and H. Pearson, 243-270. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

- Sahlins, M. D. 1963. Poor Man, Rich Man, Big-Man, Chief: Political Types in Melanesia and Polynesia. Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 5, No. 3:285-303.

- Strathern, A. 1971. The rope of moka. Big-men and ceremonial exchange in Mount Hagen, New Guinea. Cambridge studies in social anthropology 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)