|

|

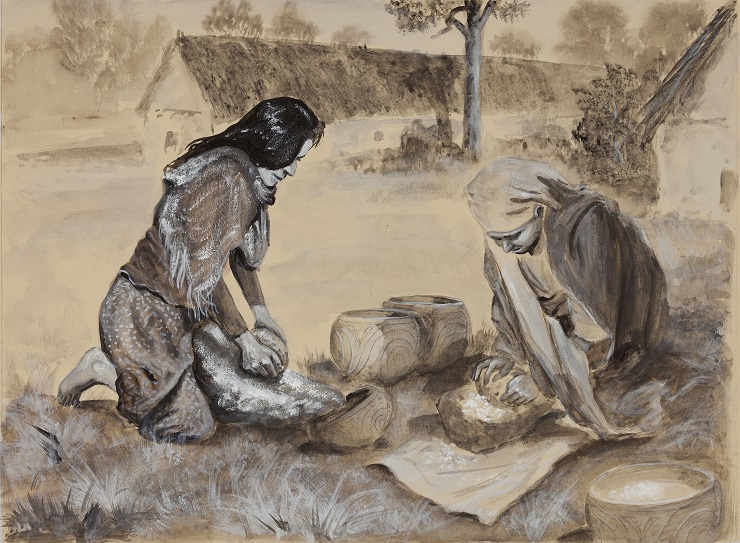

| The work with grinding tools obviously constituted a tiring daily routine. In addition to experience and a habitual working position, it also required a certain knack in regard to handling. At the same time it could also be a social occasion, during which important news and life experiences could be shared. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

Grain grinders, crushers, friction blocks, grinders - these are all names of stone grinding tools that were encountered in finding files relevant in regard it at least the last twenty thousand years. Increased concentration concerning the various shape types of these “simple devices” represents one of the important signals of change in everyday dietary habits in the area of Near East from the 12th millennium BC - especially in regard to the preparation of plant foods, especially grains but also of other parts of plants, such as their leaves and their roots. Grinding tools, even simple grinders, did not become an integral part of the equipment used by prehistoric communities till the 10th millennium BC, i.e. the period for which we use the term Neolithic. Although in scientific publications the grinders represent an important item of the Neolithic package, this does not mean that these tools were previously unknown in the hunter-gatherer societies.

|

| The passive (static) lower tool and the active upper tool (the runner) together constituted a simple grinding device. Starting from the Neolithic period this equipment represents a normal part of the finding files. A replica of the grinding equipment displayed in the permanent exhibition of the Museum of West Bohemia in Pilsen. Photo by Tereza Blažková 2014. |

They are very simple manual devices consisting of massive lower (static) stones and the upper stones (the runners); runners were driven by direct or the circular movement of dexterous hands of especially those of the female population in the prehistoric settlements. The lower rough-hewn stones were usually either laid directly on the ground or they were permanently embedded in the base that was made from daub. Their shape was adapted on order that the thicker (higher) end of the device could be placed closer to its operator and the processed product was fed from the far end either onto the ground or into a container. The length of the lower stone usually did not exceed half a metre, while its width was cca. 30 cm. The upper stone was max. 20 cm wide and usually longer (up to 40 cm) than the width of the lower stone, which made it easier to handle and also enabled the use of the entire surface of the lower stone for grinding. The lateral handles on the upper part of the equipment were ergonomically adjusted for a more comfortable grip.

The finding situations in which grinders are discovered may vary, but usually they represent classic settlement refuse. The manner of the use of grinders and their utilisation within the social framework of prehistoric communities have been addressed by archaeologists on the basis of their shape, their metric, technological and resource designation in conjunction with the specific context in which these artefacts were found. Important, of course, are ethnographic analogies, though the utilisation of research from other geographic environments and eras can conceal a number of problems.

|

|

| Quartz porphyry (paleorhyolite) that is still quarried to this day close to Malé Žernoseky (a district of Litoměřice) had the ideal characteristics for the production of prehistoric grinding tools. From the Neolithic period the slabs with appropriate dimensions have been quarried in the near-surface solid rock, which can be adjusted in a relatively short time by chipping it into a rough shape. The quarry area belongs to Kubo s.r.o. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2013. |

|

|

| Using stone tools the experimenter managed to shape a replica of the runner within two hours. How long would it have taken experienced manufacturers? Apparently the final shaping of the tools would be carried out directly in the settlements. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2013. |

|

|

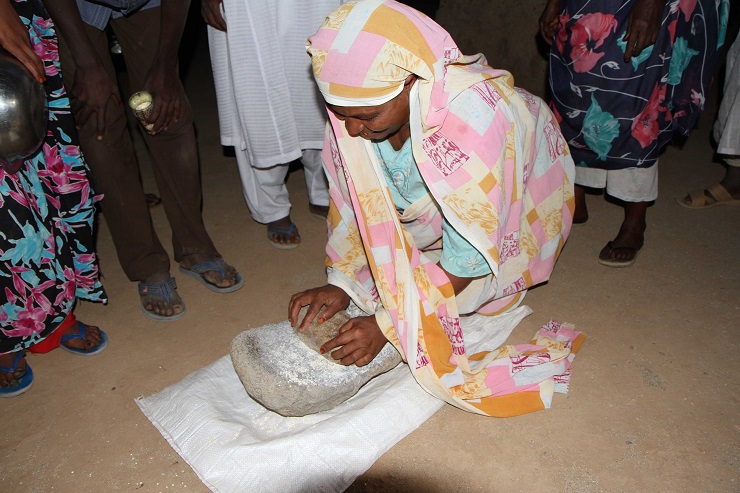

| In central Sudan stone grinding machines are no longer widely used. This picture comes from a wedding ceremony that took place in the Muslim community, during which the women and the men of different generations alternate with the grinding. Research by the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague. Photo by Ladislav Varadzin 2012. |

Want to learn more?

- Adams, J. L. 2002. Ground Stone Analysis. A Technological Approach. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

- Hamon, C. 2008. Functional analysis of stone grinding and polishing tools from the earliest Neolithic of north-western Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science 35/6:1502-1520.

- Hamon, C. – Graefe, J. eds. 2008: New Perspectives on Querns in Neolithic Societies. Archaologische Berichte 23. Bonn.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)