There is a series of events that started to occur in the Neolithic period both for the first time and also complementarily; burying does not belong amongst them, however. The deliberate storage of human remains in grave pits, shallow beds or caves occurred already during the Middle Palaeolithic, suggesting that then, cca. 80,000 years ago, human thinking already had an abstract character. What do the burials show us? In addition to altering the perception of the outside world, perhaps also the belief in another dimension, or the need to protect the living from the dead, it could also indicate a pragmatic hygiene standard that would be required for the long-term usage of just one place in the landscape. The addition of flowers to the graves of the Neanderthals from the Shanidar Cave or the frequent use of red pigment in Palaeolithic graves both indicate some form of ritual burial. The subsequent Mesolithic period is much more modest in regard to the burying of human remains.

|

| Dead men of the early Central European farmers were usually buried on their left side in a strictly crouching position. In the case of burial at the Hoštka site (district of Litoměřice) additions comprised a stone cosh and a container from the middle stage of the Linear Pottery culture (According to Zápotocká 1998, Bestattungsritus ... 182, Tab. 9 B). |

For the sedentary Neolithic society the burial rite follows the basic rules in regard to its function. From the ethnographic evidence that is available we know that there is a considerable variety of ways in which the body of the deceased could be treated, and that reverent behaviour is always culturally relative. It is likely that the Neolithic communities of the temperate European belt did not confess any burial creed and that it depended rather on the specific population involved. Only two ways of burying were found to be beyond the edge of Neolithic visibility: inhumation, whereby the mortal remains are stored in the earth, and cremation, whereby the deceased is first burned and only subsequently his/her ashes are buried.

More typical is inhumation whereby bodies were either stored in burial pits located at burial grounds or in settlement pits and less frequently in caves or in circular ditches, etc. It is not clear what these individual practices testify to. Typical of regular burials is a crouching position, more frequently on the left side, with the head towards the east, but other positions were also documented. Additions to the grave usually have the form of ceramic vessels, the stone industry, ornaments made from animal bones and teeth, the shells of either freshwater or marine bivalves. In comparison with the number of settlements that exist large-scale burial sites in the Czech Republic and also in Europe can be found only sporadically.

|

| The burial of the girl in the trench located by the large roundel in Kolín. The skull of this girl shows evidence of a blunt injury to the skull, which was probably the cause of death. The anthropological facial reconstruction of the deceased gives us an imaginative opportunity to look this woman in the face. Grave 165, Kolín - Area I, the Stroked Pottery culture. |

Cremation burials in our country were found to be taking place at the burial site in Kralice in Haná. Cremation is more common, however, during the subsequent period of the Stroked Pottery culture. An unanswered question remains in regard to the empty pits at the burial sites where there are also visible signs of the disturbance of the original status. It could be about a document of burial that we are not yet able to identify. The bodies, for example, may be wrapped in an animal skin and later they would be removed from the grave pit; where they would have been transmitted, is not at all clear, however. Partial response could be provided based on the findings from Herxheim. We know about the largest number of empty graves from Germany, but this also occurs at the burial site located in Vedrovice, for example.

The different forms of burial can be interpreted in the context of a socio-economic reflection of Neolithic society, but this is not necessarily the only possible interpretation. There is also a need to take into account the personal dimension of family ties, close relationship to the deceased and other topics. Any of these factors could influence the processes of commemoration and of burial (it could, for example, lead to the intentional breaking of items that constituted part of the personal property of the deceased, as it is documented in ethnographic cases). The presence of only part of a vessel or of another item could be explained as holding on to a reminder of a nearest and dearest. In this context, the frequent variability of the burial rite is easy enough to understand but hard to grasp in accordance with a uniform normative.

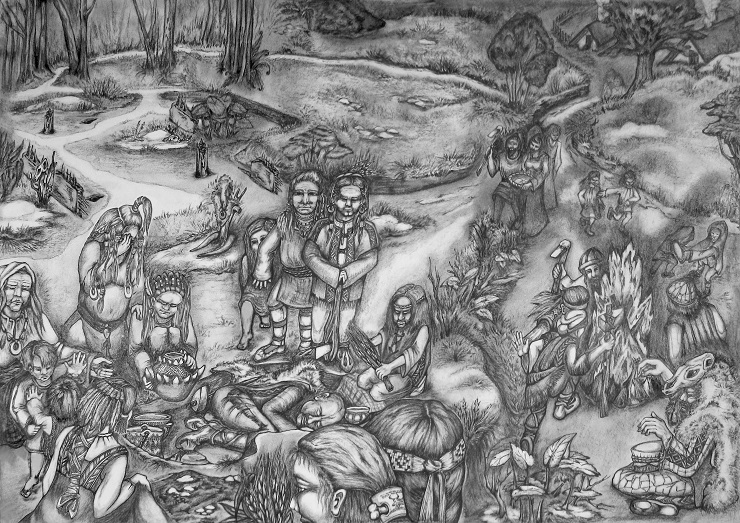

|

| The artistic imagining of burial ritual taking place in the Neolithic community. While the archaeological visibility is restricted to the actual preserved grave and the buried party in it, in fact, the sad event of this kind was actually accompanied by many spiritual activities of which we were able to decipher only very little. |

Want to learn more?

- Hofmann, D. 2009. Cemetery and settlement burials in the Lower Bavarian LBK. In Creating Communities. New advances in Central European Neolithic research, eds. D. Hofmann, and P. Bickle, 220–234. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Jacobi, F. 2011. Die Gründer von Schwanfeld und andere bandkeramische Bestattungen – Was uns die Toten über das steinzeitliche Leben erzählen können – Die Bestattungen aus Schwanfeld. Frankenland 6: 415–422.

- Lenneis, E. 2010. Empty graves in LBK cemeteries – indications of special burial practises. Documenta Praehistorica 37: 161–166.

- Lüning, J. 2011. Gründergrab und Opfergrab: Zwei Bestattungen in der ältestbandkeramischen Siedlung Schwanfeld, Lkr. Schweinfurt, Unterfranken. In Schwanfeldstudien zur Ältesten Bandkeramik. Universitätsforschung zur prähistorischen Archäologie, ed. J. Lüning, 7–100. Bonn: Habelt.

- Maschio, T. 1994. To Remember the Faces of the Dead: The Plenitude of Memory in Southwestern New Britain. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Nieszery, N. 1995. Linearbandkeramische Gräberfelder in Bayern. Internationale Archäologie. Espelkampf: Leidorf.

- Zápotocká, M. 1998. Bestattungsritus des böhmischen Neolithikums (5000–4200 B. C.). Gräber und Gräberfelder der Kultur mit Linear-, Stichband- und Lengyel-Keramik. Praha: Archeologický ústav AV ČR.

- Zvelebil, M., and P. Pettitt. 2008. Human condition, life and death at an early neolithic settlement: bioarchaeological analyses of the Vedrovice cemetery and their biosocial implications for the spread of agriculture in central Europe. Anthropologie 46 (2–3).

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)