|

| Containers made of organic materials in the Neolithic certainly represented an important portion both of the transport and the storage containers. Finding situations in wells can often lead to the preservation of these otherwise substantially invisible archaeological artefacts. In the picture there are the vessels related to the ethnographic context of Sudan. On the left there is a basket so densely wickered that the container even retains fluid. On the right there is a gourd bottle, which, for operational reasons, is bandaged with leather straps. |

A source of drinking water is an essential feature of any settlement and this was as applicable in Neolithic times as it is today. Water from flowing streams or rivers may not always be suitable for the purposes of cooking or of quenching thirst and for that reason wells were built in the areas of the settlements of the early Neolithic farmers. Dating back to the period of 7,000 years ago they represent the oldest evidence of the existence of facilities of this nature in Central Europe.

Although Neolithic wells belong amongst the very rare archaeological finds, they constitute, literally, a repository of knowledge of that period. Their importance lies particularly in their capability to preserve such organic materials such wood, bark or bast. They demonstrate to us the sophistication of carpentry construction and the use of containers made of different materials than ceramic clay. They also allow us to examine the composition of plant macrofossils that enable us to imagine the precedents of the agricultural landscape. The last, but not least, benefit from findings wells is obtaining dendrochronological data that clearly dates the year of the felling of the trees that were utilised during their construction. In our area we know of only three wells – one in Mohelnice, one in Most and a recently unearthed well located in Brno-Bohunice. Nearly thirty of them have been explored, while in Europe, while their accumulation in East Germany is exceptional.

|

|

| Neolithic wells representing the expansion of the Linear Pottery culture. Adapted from Elburg 2011 Tegel et al. 2012. |

The Neolithic well constituted pit that was dug, using a bone, an antler or most frequently wooden tools, to below the level of the groundwater. Their actual inner structure could differ – usually the walls were reinforced with timbering in various forms (e.g. in Eythra 1, Mohelnice, Rehmsdorf, Brodau, etc.), but this was not a rule (e.g. in Brno-Bohunice, Most, etc.). The water was pump into ceramic pots, bottles, containers made from birch bark or bast. It is these findings from the infill of wells that show us a number of items that otherwise, within the normal settlement conditions, we do not have any chance to find. Apparently the water was pulled up using a pulley system; this can be documented, for example, by finding the imprints of two poles outside the mouth of the well in Erkelenz-Kückhoven and a portion of the crossbar with grooves from the rope from its infill.

|

|

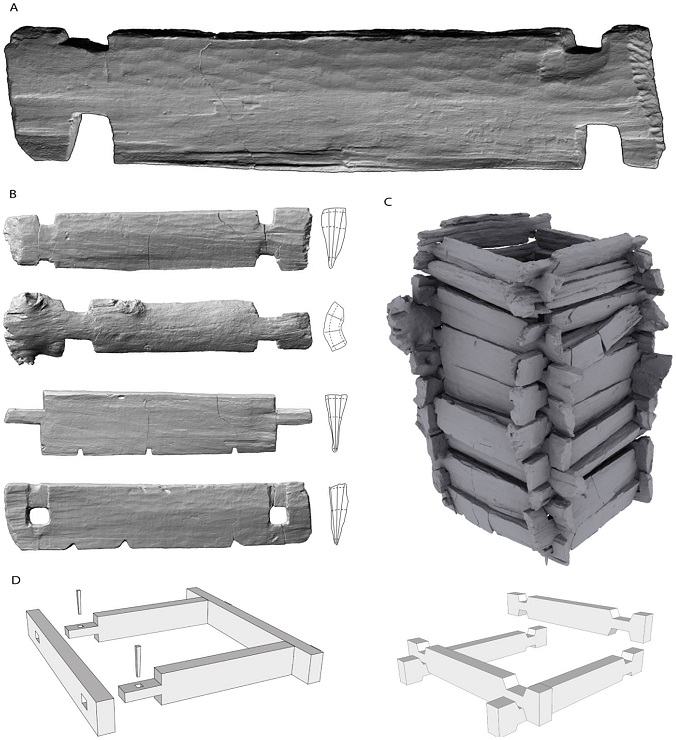

| A digital model of the well (C) in Eythra 1 that was generated during a survey using a 3D laser scanning of the timbering shows the skills of the Neolithic craftsmen. Clearly visible on the surfaces of the boards (A) there are traces that were left by the stone working tools. The different types of joints made and the processing of the individual planks (B) demonstrate the sophistication of their creators. A drawing of the carpentry joints utilised for the timbering of wells (D) using pin connections secured by wedges and a frame connected to the interlocking corner parts (i.e. cogging). Figure taken from Tegel et al. 2012. |

Why were the wells actually needed in the Neolithic? The reasons may vary. Although the settlements were mostly built in the vicinity of watercourse (usually not further away than 300 metres), the presence of a well directly in the settlement definitely might make life more comfortable. Some kind of short-term reservoir or recessed trenches along the walls of houses could also serve as water reservoirs, however. The reason for the construction of wells might also have been the insufficient purity or quantity of the surface water, which could also have been influenced by fluctuations in the weather. It appears, however, that one well (on most of the settlements usually only one was discovered) was sufficient as the sole source of water for the entire settlement. Another question also concerns the iconic significance of water sources and the sanctity of water, which we are familiar with from many other (including archaic) cultures.

|

|

| A bottle-shaped container of the Linear Pottery culture, its neck bandaged with a rope, which apparently enables the pumping of water. Also clearly visible is the place where the broken vessel was repaired, which was mended by using pitch and bark. The container comes from one of the wells in Eythra, Kreis Leipzig © Landesamt für Archäologie Sachsen. Photo by J. Lipták. |

|

|

| Ceramic pots of the Linear Pottery culture from the well in Altscherbitz, Flughafen Leipzig / Halle, Kreis Nordsachsen © Landesamt für Archäologie Sachsen. The first is decorated with a resinous paint and bark inlay, while the second has a spiral decoration implemented by using a resinous coating. |

Want to learn more?

- Anýž, R., M. Slezák, M. Štěpán, R. Thér, and R. Tichý. 2002. Konstrukce studny v Centru experimentální archeologie Všestary. Živá archeologie – (Re)konstrukce a experiment v archeologii 3: 83–104.

- Elburg, R. 2011. Weihwasser oder Brauchwasser? Einige Gedanken zur Funktion bandkeramischer Brunnen. Archäologische Informationen 34 (1): 25–37.

- Pavlů, I. 2008. Voda v neolitickém domě. Živá archeologie – (Re)konstrukce a experiment v archeologii 9: 7–8.

- Přichystal, M. 2008. Brno (k. ú. Bohunice, Nový a Starý Lískovec, okr. Brno-město). In Život a smrt v mladší době kamenné, ed. Z. Čižmář, 50–59. Brno: Ústav archeologické památkové péče Brno.

- Rulf, J., and T. Velímský. 1993. A neolithic well from Most. Archeologické rozhledy 45 (4): 545–560.

- Stolz, D. 2004. Neolitické studny se zachovanou dřevěnou konstrukcí a jejich organický obsah – fascinující pohled do zmizelého světa. Živá archeologie – (Re)konstrukce a experiment v archeologii 5: 29–48.

- Tegel, W., R. Elburg, D. Hakelberg, H. Stäuble, and U. Büntgen. 2012. Early Neolithic Water Wells Reveal the World´s Oldest Wood Architecture. PLOS ONE 7 (12): e51374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051374.

- Koschik, H. (ed.) 1998. Brunnen der Jungsteinzeit. Internationales Symposium Erkelenz 27. bis 29. Oktober 1997. Köln/Bonn: Rheinland-Verlag GmbH.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)