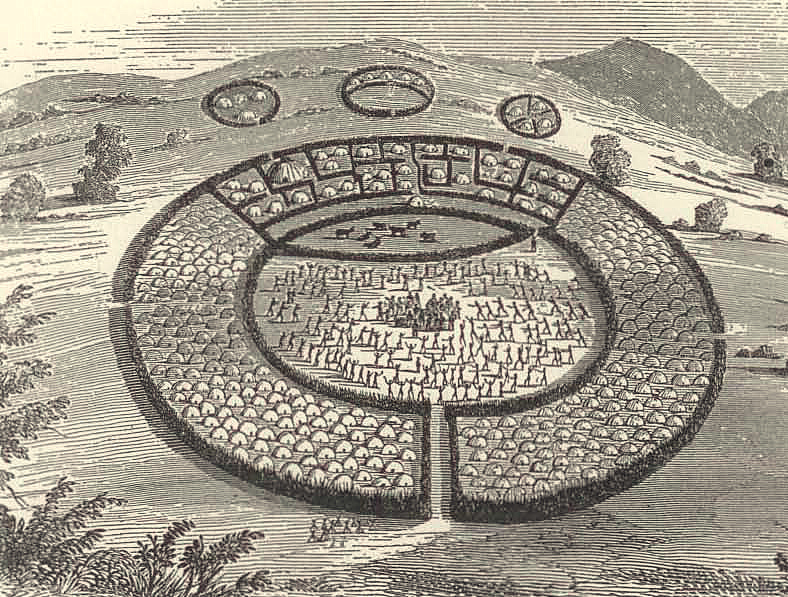

In 1824, the English merchant and adventurer Henry Fynn set out on a journey into the unknown and obscure Zulu Empire. The area of the Bulawayo royal settlement where there were thousands of homes around the huge square, all in the shape of beehives, surprised not only himself but also the group of white travellers who had accompanied him to South Africa.

|

|

The residential Zulu town of Bulawayo in 1824. Henry Fynn witnessed a parade of 80,000 soldiers of the Imperial Army of the black King Shaka in the central kraal. |

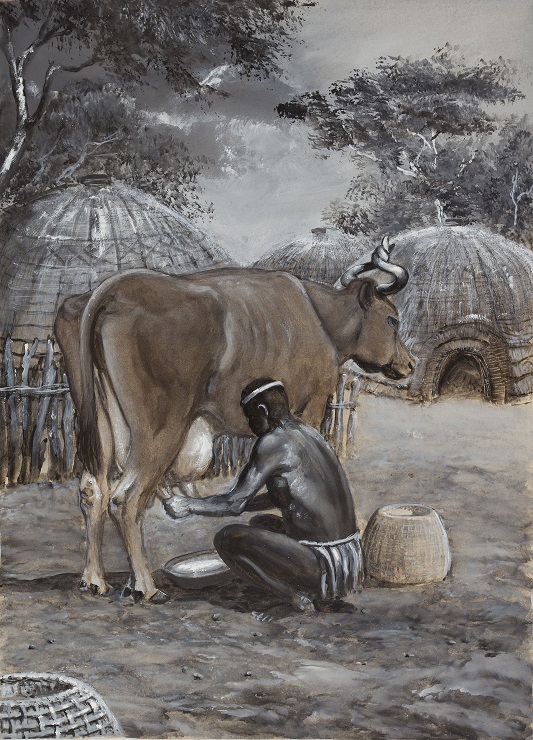

Zulus originally constituted one of the many small clans that belonged to the larger Nguni population. Similarly to the other linguistic groups in the South African, this was a society with a pastoral economy that was supplemented by the cultivation of agricultural crops. In the gardens close to the settlements the women mainly planted corn, which was imported to the African continent by Europeans. Land cultivation was carried out manually using digging sticks, which in the absence of irrigation was extremely difficult. Amongst the Zulus cattle breeding, milking cows and hunting big game were all considered as being honourable activities and for this reason they were usually carried out by men.

Much more important than crops, in terms of livelihood, social status and also as the subject of economic transactions, was cattle. For their protection against wild beasts kraals were constructed, i.e. circular corrals that were located in the centre of each homestead. Every night the herd was enclosed there, while during day the animals grazed outside. Cattle were extremely highly valued, because the size of the herd represented a benchmark of social success for every man. Not only the number but also the physical condition of the animals was a subject of never-ending interest. The owners strived after a unique look for their cows and their bulls, so not only did they decorate them, but often they also deformed their horns into bizarre shapes. The significance that the cattle had for the Nguni suggests that the natives only rarely slaughtered their animals. This was carried out exclusively in connection with festivities and for very special family events.

|

|

| Typical manifestations of the Nguni care of cattle included the aesthetic deformation of bull and cow horns. Each owner sought for the individual appearance of their own favourite animal. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

The Nguni settlement structure had close ties to social organisation. Its basic units were smaller villages or individual homesteads. These were called umuzi and they were inhabited by a kinship circle, at the centre of which was the oldest man, some sort of patriarch. The daily activities were governed in accordance with the customary canon, which in practice meant that most of the work was actually done by women. Each of the settlements was economically independent and, at fundamental level, also legally independent, which meant that any disputes that occurred between residents were ultimately resolved by the patriarch. The individual umuzis were socially merged to create larger units that could be defined as clans. Each clan had its own chieftain, whose position was derived from his hereditary kinship with the ancient, frequently mythological, ancestor and founder of the clan.

|

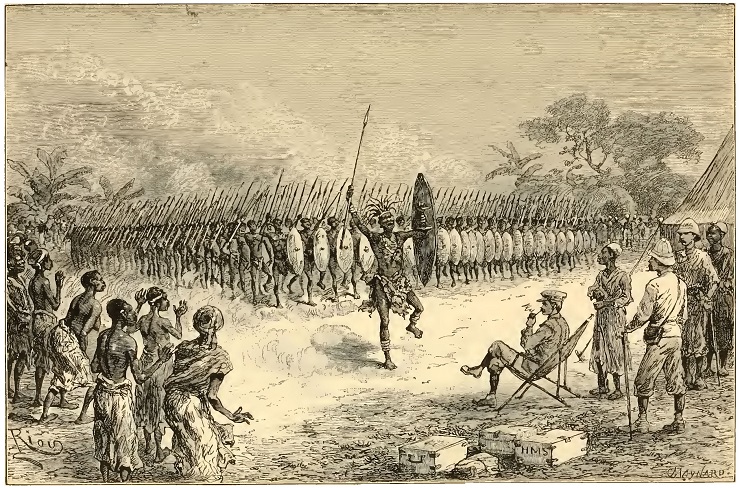

| The breathtaking impression that the discipline of the tribal fighters in Mozambique made on the traveller, H. M. Stanley, evokes the same feeling that an organised mass of Zulu warriors evokes in Europeans. According to Stanley, 1891, 439. |

There were a large number of clans throughout the territory that was inhabited by black pastoralists. Assets were always inherited by the eldest son who had been sired by the Big Mother (i.e. the woman whom the man had married in adulthood, when he had already gained a proper position). The system of the hereditary redistribution of wealth and social status created an explosive environment of social imbalance. On one side of the Nguni society there was a class of rich and noble owners of herds, while, on the other side, there was a larger group of poor individuals, who did not own any cattle and lived in a sort of “lease” of their wealthy patrons. Opportunities for how to enrich himself and his clan at the expense of others were mainly warfare, which during the classic period became a highly ritualised phenomenon. The result was the establishment of a hierarchy between the clans that also included the transfer of herds of cattle.

It is interesting that in the 19th Century two specific rulers, Dingiswayo and Shaka, both managed to create, from an originally small pastoral society numbering perhaps several hundred people, an empire of a million citizens together with a powerful army. Although the Zulu Empire did not survive the 19th Century, this great nation does still exist today. Shaka’s policy was very aggressive – as a consequence of the fighting and of hunger a million natives died in the areas to the west and the northwest of the Drakensberg Mountains. The cruelty and the madness of the king eventually led to his murder in 1828. The independent Zulu Empire existed another 50 years, however, until it inevitably succumbed to the pressure of the European colonialists.

Although some researchers previously thought that the local kings had been inspired by the colonialists and therefore they would be able to unite their vast territory, it appears that the essence of this phenomenon is some sort of combination of environmental conditions and also, in particular, the local economic and social organisation of the Nguni herders. At the very outset, prior to creating the empire, both political and proprietary turbulence were common; the core conflict, as usual, concerned herds of cows. A kind of revolution began, however, that provoked irreversible social changes, which actually mainly benefited former outsiders. The spoils of war brought them wealth and thereby also the social status within their domestic clans that they desired. While, at the same time, they, in gratitude, supported the king who had assigned their functions to them.

|

|

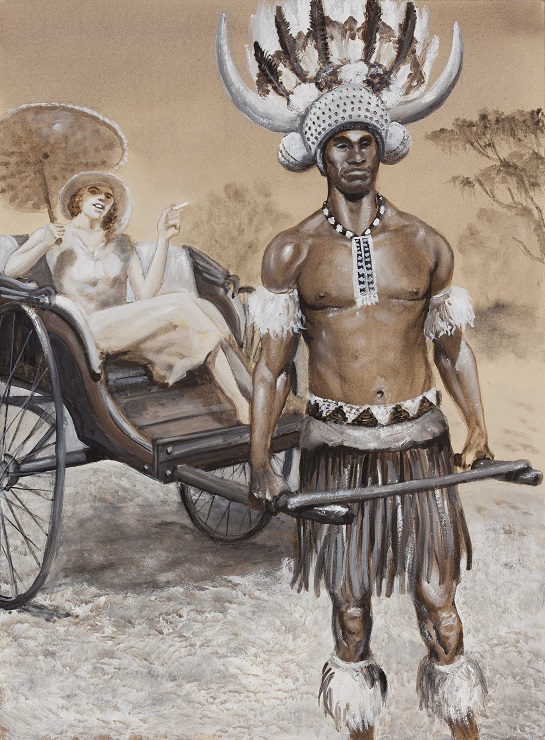

| At the cusp of the 18th and the 19th Centuries the Zulus created a strong state in South Africa, which went on to conquer many of the local tribes. For some time their empire even resisted the colonial attempts of Britain when, in 1879, the Zulu warriors succeeded to win the Battle of Isandlwana. By the beginning of the 20th Century, however, there was nothing left of the previously mighty empire and he who was once a proud warrior serves as a rickshaw driver for a white lady. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

The emergence of the Zulu state in South Africa is the type of process that lies at the historic interpretive border between the colonial inventiveness and the native dynamism of the African social environment. Whether when describing the changes we focus on the hard-to-balance system of the local social hierarchy and its values, or whether we take more notice of external factors in the form of European influences or focus on the heroic roles of Dingiswayo and Shaka, the history of black kings remains a kind of laboratory example of the creation of one specific ethnic group. Though after 80 years of its existence the Zulu Empire ceased to exist, its legacy continues to persists: when the period of the chieftain clans ended was when the nation was actually born.

Want to learn more?

- Fynn, H. F., J. Stuart, and D. M. Malcolm. 1950. The Diary of Henry Francis Fynn. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: Shuter and Shooter.

- Gluckman, M. 1955. The Kingdom of the Zulu of South Africa. In African Political Systems, eds. M. Fortes, and E. E. Evans-Pritchard. London: Oxford University Press.

- Gluckman, M. 1960. The Rise of a Zulu Empire. Scientific American 202 (4 (April)):157-168.

- Chanaiwa, D. S. 1980. The Zulu Revolution: State Formation in a Pastoralist Society. African Studies Review 23/3:1-20.

- Mathieu, D. 1999. Warfare, political leadership, and state formation: The case of the Zulu Kingdom, 1808-1879. Ethnology 38 (4):371-391.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)