|

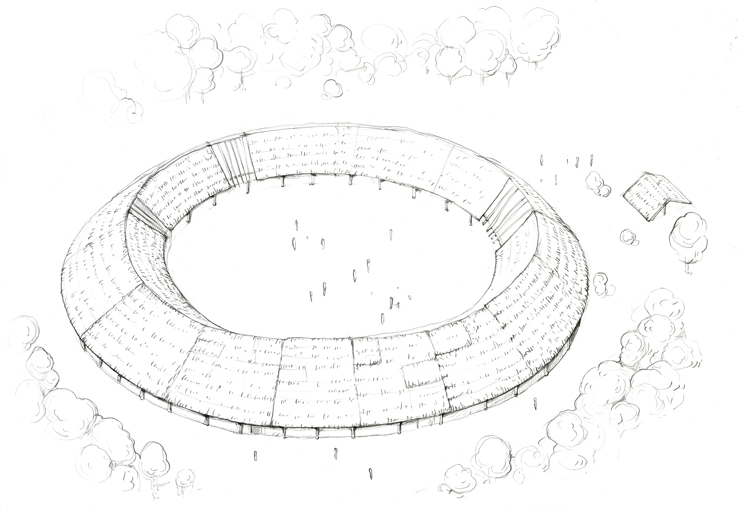

| The Shabono represents the house and the village in one. The entire residential community lived there, all under the same roof. Drawing by Martin Černý. |

The anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon was engaged in the field research of the Yanomamö forest population living in the tropical region of southern Venezuela and also in the adjacent areas of Brazil. For a long time the Yanomamö culture had only a very limited contact with modern Western civilisation and therefore, until the early 1960’s, it was able to preserve its traditional character including only the minimal use of metallic objects. In terms of its social characteristics it was an egalitarian tribal society economically based on forest agriculture. It took the form of slash and burn gardening, which led to the premature exhaustion of the soil, so that subsequently the alternating cultivation of different plots was practiced.

The villagers lived in a communal manner, which was largely due to the fact that the entire village community lived under one roof in a specific structure that was called the shabono. The structure was characterised by its oval layout and its diameter of cca. 90 m and its open central area. Where the populated area was not enclosed by stockade fencing, the outer wall of the shabono also constituted the boundary of the settlement.

The settlement pattern in the area consisted of some dozens of villages, each of which usually had fewer than 200 inhabitants who all belonged to just two or three lineages. These kinship groups formed the basis of the Yanomamö’s social and political organisation, whereby the oldest adult male of the strongest (or largest) clan also served as the village head and often also as its shaman. He needed to be not only physically and morally strong, but to also have spiritual powers. He administered a village of 100 to 200 souls; in the case of larger populations, splits frequently occurred in the village as a result of disputes. The leader also asserted his authority in relation to the surrounding villages in the manner of organising war expeditions.

|

| The Yanomamö men practiced hunting in the jungle using bows and arrows that were frequently poisoned. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

The fibres of social relations were mostly spun and linked together in association with festivities, at which usually the members of more than one community met and which, amongst others, represented an opportunity welcomed by the men to show-off their war gear. The most common form of celebrations of this nature was feasting, the organisation of which, on the one hand, was very prestigious, while on the other hand it was also quite expensive, so that only a wealthy man could afford to act as the host. The material culture of the Yanomamö was simple and was produced mainly from domestic sources. Exchange took place mainly in the form of non-violent contacts between different communities.

The basis of the Yanomamö’s subsistence economy was the crops that were cultivated, which accounted for more than three quarters of all the food that they consumed. Therefore great attention was paid to caring for the cultivated area. All of this was initiated by the selection of suitable sites for the establishment of a new garden in the jungle. It had to be an area into which more natural sunlight penetrated and, if possible, with a sparser amount of vegetation in the shrub-layer. The drainage characteristics of the land were also considered as being of great importance. The initial preparational phase of the selected areas of the forest was directed entirely by men and after making adjustments to the land areas, the men divided it amongst themselves.

Sometime up to four garden areas were in use, all located in different directions from the village. Distinguished in regard to gardens that had been used for several years was the older part, referred to as the butt, and the newer part, referred to as the nose. This newer part was created simply by adding another newly cultivated plot of land to the original area, to which plants were then transplanted. Thereby the Yanomamö gardens moved slowly, both in space and time. The sites that had been cultivated for the longest time were eventually abandoned, because it was easier for the Indians to prepare new land than to rid themselves of the thorn bushes that had invaded the old site. Work in the gardens was carried out in accordance with a seasonal schedule, which was determined rather by social events than by the weather. During the dry season there was not much hard work done, because this was the time for celebrations, feasts, visits, exchange transactions and also for wars. Only those who were going to hold larger feasts during this season, and to impress others socially, continued their cultivation, including carrying-out heavy work operations. Most people started working regularly on the land at the time of the arrival of the rains. This was not really about a change to the rainfall regime, but rather about there being less heat. In addition, at this time of the year the fieldwork would not coincide with any festivities.

|

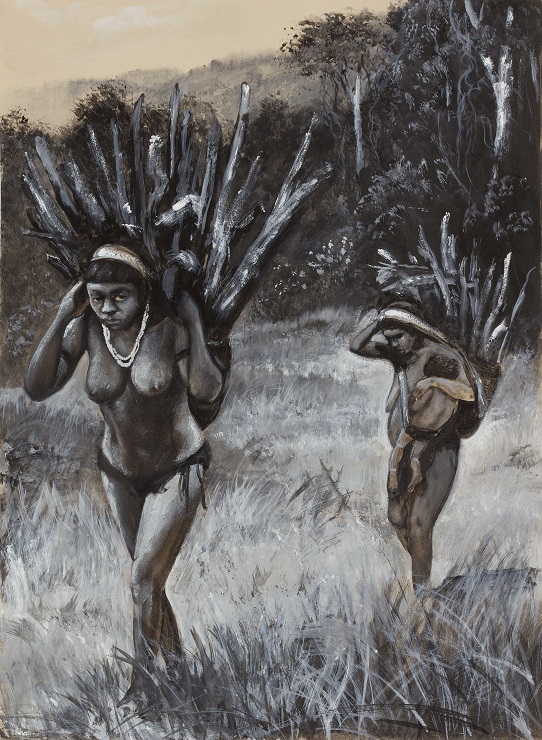

| Women of the South American Yanomamö tribe in the course of their usual activity – i.e. transporting firewood to the village. Very young children stay with their mothers, which means also during this kind of work. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

On each plot three or four species of cultivated crops were grown, of which one was always bananas, often in several varieties, while the larger part of the garden beds was dedicated to cassava. Other important crops that were grown were taro, yams, sweet potatoes, corn, several different fruits, tobacco, gourds and cotton. Additional sources of food were hunting, fishing and gathering. The wild plants gathered provided a supplementary food component, which was also based on the seasonal occurrence of targeted fruits. In between the gathering and the hunting was the alimentary use of insects. Larvae in particular constituted a highly prized delicacy.

Want to learn more?

- Asch, T., and N. Chagnon. 1970. The Feast. Movie. 29 minutes: Documentary educational resources.

- Asch, T., and N. Chagnon. 1975. The Ax Fight. Movie. 30 minutes: Documentary educational resources.

- Chagnon, N. 1968. Yanomamö: The fierce people. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Chagnon, N. 1973. Daily Life Among the Yanomamö. In You and others. Readings in Introductory Anthropology, eds. A. K. Romney, and P. L. DeVore, 49-59. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Winthrop Publishers.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)