The only source of information about ancient preliterate societies is their belongings. To understand the function that they had in the defunct culture correctly is not easy at all. While it is surprisingly not precluded by the differences between their culture and ours, the problem is in formative processes. We are seriously disadvantaged by only being able to describe and subsequently analyse those items and their characteristics that have been preserved. And not only that! Only in a negligible number of cases are objects from the past found in the condition in which they were used and also in the location where this took place. Such exceptional finding circumstances can be likened to the status of the ancient City of Pompeii that vanished suddenly during the volcanic eruption that took place on the 24th August, 79 AD. All the buildings and the tangible objects in the City were conserved by the volcanic dust in their original condition in which people used them. Time-resistant capsules of this type are generated only in extremely rare cases, however.

|

|

|

Evidence of lateral cycling of a specific type: a merchant vessel adapted for operations in Arctic Glacier Enterprise with its home-port in Seattle was sold to a new Russian owner from Murmansk. Photo by Petr Květina, Tromsø 2008. |

On the other hand archaeologists regularly encounter items that, although they were originally part of a living culture, already at the time of its existence they had been abandoned. Movables that were no longer needed or were worn out appeared in the refuse while immovable objects were left behind and abandoned to their fate. In these situations, a lot of artefacts and other property irretrievably disappeared, together with the relationships that had linked the items to each other in the same semantic category. A basic but a reasonable example is toothpaste and a toothbrush, which are regularly together in a functional context, whereas we are not likely to find them together on a scrap heap. Between the culture of living things and that of mute archaeological findings there exists a black box of formative processes that the artefacts went through both during their life and subsequent to their demise.

|

|

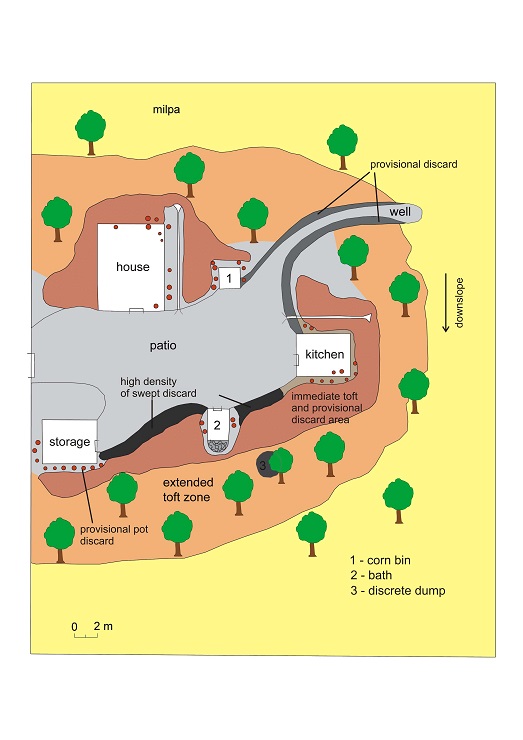

| Eccentric depositing of refuse illustrated by the example of a village of Mayan farmers that is called Tzeltal. See also “depositing of temporary refuse for which its further use is expected. (Deal, 1985, 252). |

Between the artefact’s production stage and its discarding several other processes take place such as reutilisation (after the termination of their primary function the item may be used for another purpose, e.g. a t-shirt can be used as a rag), recycling (also known today; while in prehistoric times, for example, pottery shards were added to clay as a filler material) or passed on for lateral cycling (the items start to be used by someone else somewhere else). Decoding the original context of a living culture also depends on the manner of the final discarding of the item. There is primary refuse which is left wherever it stopped serving a purpose, but usually every human society must somehow address the issue of its refuse. Another option is the use of items that have been deposited for whatever reason, be it ritual or practical, that have either been left at a specific location deliberately or that were simply forgotten.

The most common type of refuse is secondary refuse, while the deposition location is different from the place where people made use of the items. It is a typical product of settled societies that require a higher degree of organisation of space. There are spatially defined areas for the accumulation of refuse (i.e. scrap heaps) that are important for maintaining a certain level of comfort in the settlement. All the previous links between things and people’s lives are severed in this manner however. Despite this, archaeologists do still try to find a way in which to decipher the original significance of discarded items. This is actually one of the essential big questions of Archaeology – as a field that considers itself as being a professional discipline for obtaining information directly from the items themselves. It is obvious that a quantity of data can be obtained from an analysis of the preserved remains, especially in connection with the circumstances based on which they have been preserved. In reality, however, the interpretation of remnants of the material culture of archaic societies is, without exception, based on the key principle of similarity.

Archaeologists have begun to take into account for their work the world of the more recent pre-industrial societies. This cooperation has been evolving since the 1960’s, especially in the Anglophone transatlantic areas. Ethnographic analogies offer assistance not only in regard to the individual artefact domains, but also to the overall view of the manner of thinking and doing of archaic humans. This leads to the linking together of several disciplines. Ethnography is involved in the detailed research of individual cases and explains as the first the time plane dedicated to human life and the events that accompany it. Ethnology, which can systematically compare ethnographic cases and meld them into the form of cultural and social patterns, can cope very effectively with the median plane of time and society. Archaeology and History then become specialists in episodes of long duration by recognising the slow, but still very significant changes that affect our norms, our institutions and our technologies.

|

|

| The typical situation in settlement mounds located in the Near East: the current houses stand on the ruins of previous buildings, the history of which can date back as many as thousands of years. |

Want to learn more?

- Barfield, T. 2008. Archaeology as anthropology of the long term. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 13/1:41-49.

- Binford, L. R. 1962. Archaeology as anthropology. American antiquity 28:217-225.

- Binford, L. R. 1983. In pursuit of the past: decoding the archaeological record. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Gosden, Ch. 1999. Anthropology & Archaeology. A changing relationship. London and New York: Routledge.

- Harris, M. 1976. History and significance of the Emic/Etic Distinction. Annual Review of Anthropology 5:329-350.

- Hayden, B., and A. Cannon. 1983. Where the Garbage Goes: Refuse Disposal in the Maya Highlands. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 2/2:117-163.

- Nichols, D. L., R. A. Joyce, and S. D. Gillespie. 2003. Is Archaeology Anthropology? Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 13/1 (Special Issue: Archeology Is Anthropology):155-169.

- Roux, V. 2007. Ethnoarchaeology: A Non Historical Science of Reference Necessary for Interpreting the Past. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 14/2:153-178.

- Schiffer, M. B. 1987. Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Staski, E., and L. D. Sutro (eds). 1991. The Ethnoarchaeology of Refuse Disposal. Arizona State University Anthropological Research Papers 42. Tempe: Arizona State University.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)