General awareness of the means of subsistence of hunter-gatherers may involve two basic concepts. The first of these is that the main source of food is meat that has been obtained by hunting; meaning hunting in the full sense of the word, whereby a successful wildlife catch is the outcome of an adventurous event that includes tracking, the unobserved movement of the hunters through the landscape, culminating in killing the animal by means of a projectile either in the form of an arrow or a spear. The second concept gives the impression that the life of predatory bands is miserable, unilaterally focused on efforts to secure enough food to survive. It was the anthropological field research in the 1960’s that showed that a notion of this kind is not correct. Plant foods were much more significant for hunter-gatherer populations than was the meat of hunted animals. For these people obtaining food was based on a similar routine matter as that of farmers or herders. They have their available natural resources thoroughly mapped-out, so that they only have to expend a minimal effort for securing their food. The energy output expended is significantly lower than even that of the societies that are engaged in productive farming.

|

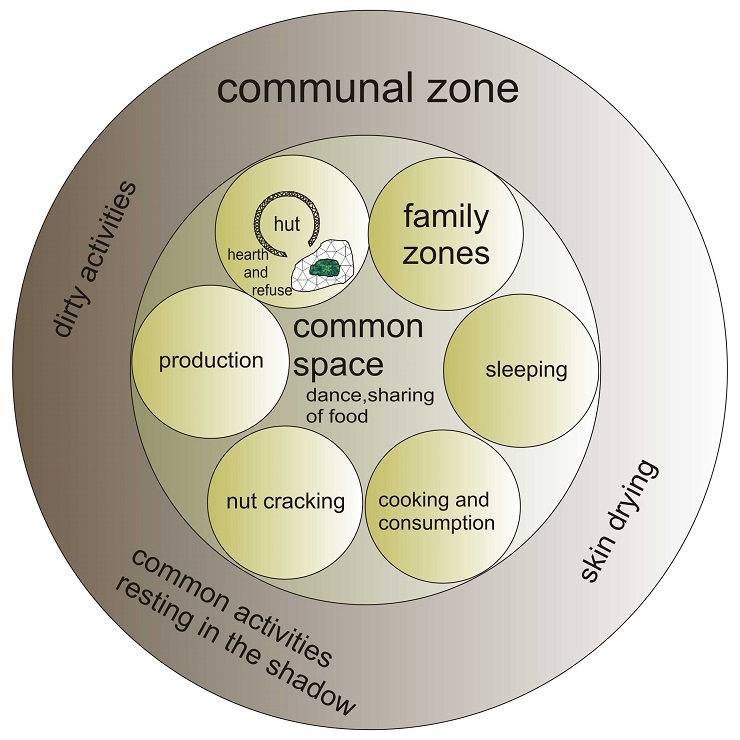

| The circular model of the Bushman camp. The smallest rings symbolise the nuclear residential zones that are usually inhabited by a family. Each of these basic spatial units contains a hut built of branches and a fireplace together with an ash dump. Within the nuclear zones activities are implemented that are associated with family life. |

One example might be the Bushmen[1] from the territory of Botswana, who inhabit the semi-desert environment of the Northwest Kalahari Desert. Contacts were already established between this population and the white population in the second half of the 19th Century. In the 1960’s a Harvard expedition went to visit one of these Bushman groups - !Kung. Interest in this population continued to increase both because of films and also the book by Marjorie Shostak on the life of local people from the perspective of a native woman named Nisa.

The Harvard expedition brought information about !Kung residents in the area of Dobe, where, in the vicinity of eight permanent pools of water, the whole population of the entire region was located, which, at that time amounted to 466 natives scattered in fourteen individual camps and at several other sites. The locals maintain contact with the neighbouring farming and herding groups. People stayed close to the water sources from May to October, i.e. during the dry season. The populated camps simply comprised loose groupings of lightweight shelters and fireplaces. The camp residents gathered together for the purpose of sharing food. The food that was brought to the camp was redistributed in order that everyone would receive his or her appropriate share. The exchanging or trading of food between individual camps took place only marginally. On the other hand, however there was very frequent movement of people between the camps.

Around each of the several inhabited camps in Dobe it would be possible to draw a circle with a diameter of nine or ten kilometres, which symbolised the economic hinterland. Within this area the plant and animal food sources were exploited intensively on an every day basis. Travelling up to ten kilometres from the camp (i.e. 20 km including the return journey) for the locals represented a common walking distance for the routine provision of a livelihood. Bushmen do not build-up a stock for a longer period of time, which means that roughly every third or fourth day they are obliged to hunt for food. 60-80% of this, in terms of its weight, comes from plant sources (mainly mongongo fruits), which is provided mostly by women two to three days a week. The men concentrate on hunting medium-size and larger game.

[1] The "Bushman" designation has been not used for quite some time because of its pejorative aspect and has been replaced by the term Sanas, with which, however, there are similar problems. The “Bushmen” did not classify themselves in any manner and only small regional groupings carried specific names. We do need a collective name, however, so we use the term Bushman, which does not have any intentional pejorative connotations.

|

|

| The Bushmen’s annual cycle. The Bushmen are moving in a regular pattern throughout the year in accordance with the availability of water resources. The availability of water also determines the size of the group and defined the activities of its members. According to Lee and DeVore, 1968. |

Leisure time is an important indicator of how much this the manner of securing food by local people demands in terms of the amount of time consumed and of energy expended. Even in the 1960’s the hunter-gatherer economy (with the emphasis on its hunting part) was considered to be extremely tough. Research has found, however, that, on average, the !Kung Bushmen spent relatively little time on securing food (i.e. 30 hours per week). How exactly did they spend most of their time then? The women were apparently capable within one working day of providing enough food for their family for the next three days, thereby giving them the opportunity to spend their remaining time in the camp. There, every day, they devoted cca. three hours to such household chores as cooking, cracking nuts, collecting firewood, carrying water... Apart from that they spent their time relaxing, embroidering, paying visits to nearby camps or vice versa receiving visits at home. The men’s activities were less stereotypical which resulted from their irregular hunting activities the pattern of which was difficult to predict. Hunters could be outside the camp for more than a week and then rest at home for an even longer period. A very important and frequent activity of the Bushmen was dancing which was closely associated with the religious sphere and with healing.

|

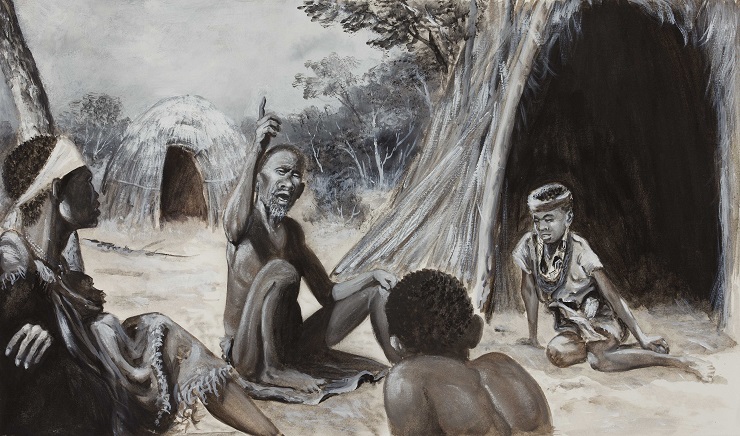

| Ui! tells the story of the great giraffe hunt. Not only the actual adventurous activities, but also telling about them gave prestige to the men-hunters in the Bushman society, regardless of the nutritional value of food obtained from hunting being significantly lower than that obtained by the food-gathering undertaken by women. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

Important was to find the evidence of the year-round availability of the source of their subsistence. Even in such a hostile environment as the Kalahari semi-desert, its predatory inhabitants had their food options well-mapped, so that they were able, in accordance with seasonal availability, to satisfy their needs from a variety of different sources. The percentage of calories consumed shows the significantly greater importance of plant food (67%) than that of meat (33%). This is also related to the gender difference in regard to the shares of the food brought-in, in the sense that the women provided a significantly larger share of food than did the men. On the other hand, it was the men who were responsible for the greater part of the volume of the meat diet. However, it was the adventurous hunting events, and even more talking about them, that gave the men-hunters in the Bushman society much greater social prestige than the women-gatherers received.

Want to learn more?

- Barnard, A. 2006. Kalahari revisionism, Vienna and the ‘indigenous peoples’ debate. Social Anthropology 14 (1):1-16.

- Fritsch, G. 1880. Die afrikanischen Buschmanner als Urrasse. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 12:289-300.

- Lee, R. B. 1967. Trance Cure of the !Kung Bushmen. Natural History 76 (9):31-37.

- Lee, R. B., and I. DeVore. 1976. Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Marshall, L. 1965. The !Kung Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert. In Peoples of Africa, ed. J. Gibbs, 241-278. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Marshall, L. 1976. The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sadr, K. 2005. Hunter-Gatherers and Herders of the Kalahari during the Late Holocene. In Desert Peoples. Archaeological Perspectives, eds. P. Veth, M. Smith, and P. Hiscock, 206-221. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Shostak, M. 1981. Nisa, the life and words of a !Kung woman. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- van der Post, L. 1958. The Lost World of the Kalahari. London: The Hogarth Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)