The geographical area of the Highlands of New Guinea is the location in which the livelihood of the natives, even in recent times, was based entirely on garden agriculture. One of the typical local societies, or more precisely an ethnographically defined group are the Bomagai-Angoiang who speak the Maring language and reside in the valley of the Simbai River.

|

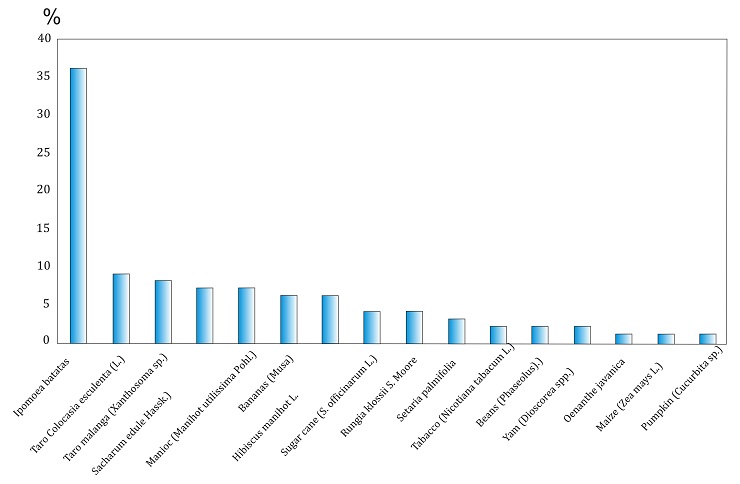

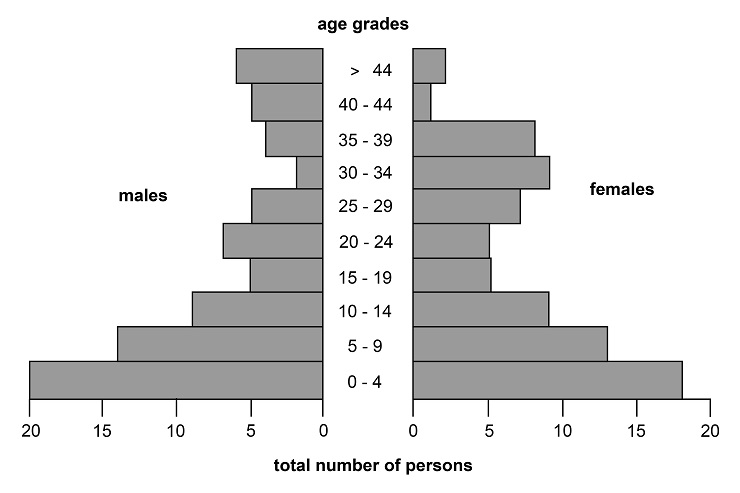

| The distribution of the population living in the basin of Ndwimba River by age and gender in early 1965. According to Clarke 1971, 19. |

They practiced garden agriculture at an altitude of cca. 1,000 metres above sea level. In location of this nature the climate was very humid, with rain occurring daily for the greater part of the year, though this did not entirely rule out the occasional occurrence of relatively drier periods. Gardens appeared in the landscape alongside the villages, including groves of fruit trees and virgin forest together with grassy areas and slopes. At first glance it appeared to be a cultivated landscape and was reminiscent of a huge park. The cultural characteristics of the New Guinea farmers were captured very well by the ethnographic probe into the Ndwimba River basin microcosm, which was carried out during the 1960’s by the Australian anthropologist William C. Clarke. It constituted an area of less than 15.5 square kilometres and was inhabited by 154 people.

The cohesion and continuity of the Bomagai-Angoiang communities over time, in practical terms, was shaped by a combination of actually belonging to the place of residence and by its kinship rules. The land belonged to the clan, the membership of which was inferred agnatically, i.e. descent was always from the father’s or the male side. But not entirely without exception, so that in the event of there being an absence of male members, the clan could also be joined by the persons that were not able to fulfil the basic rule of descendance. The clans merged to form political units of a higher order that were rather awkwardly described as clan clusters. Although the clan was formally founded on the basis of the recognition of the common ancestor, the identity of its members was perceived through sharing the settlement territory, including specific locations in the area. These locations certainly included the “Battlefield”, where regular war conflicts took place, in which the clan cluster served as an allied unit. Also, a number of ceremonies took place jointly with the clan cluster.

|

|

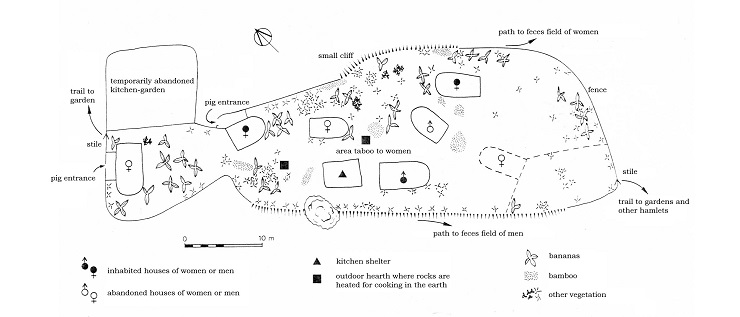

| A typical homestead of New Guinea’s Bomagai-Angoiang population. According to Clarke, 1971, 109. |

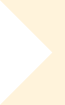

The fundamental social and economic element was the family, though the spouses did not share the roof over their heads. Women had never entered the male dwelling, whereas from time to time men did visit the women’s houses. Low huts were formed with a structure that was anchored by wooden poles and the roof was covered with grass and leaves. Promontory locations with good access to water were selected for the settlement, while the houses still remained hidden to any strange observer. The houses, the villages and the gardens were interconnected by a network of trails, which sometimes were so steep that de facto it became a narrow staircase comprised of exposed tree roots.

|

|

| A view of the Dani estates locatedin the Highlands of New Guinea in its basic parameters resembles the Bomagai-Angoiang’s settlements. The Dani also fence their homes, while their dwellings are also divided into male and female sections and for the establishment of their settlements they generally prefer higher locations. Photo by Jan Rendek, the Dani, Western New Guinea (Papua), 2008. |

|

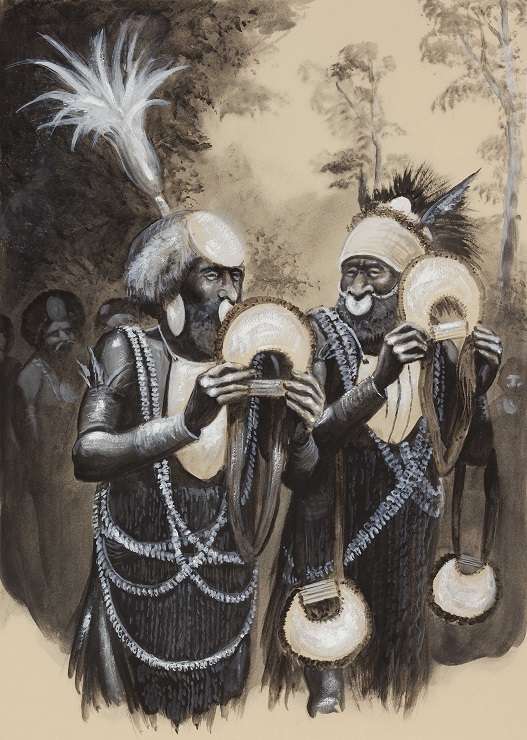

| Neither power, authority nor prestige were institutionalised in the Highlands of New Guinea nor were they transmitted hereditarily. The community leader was the man who had attained this position on the basis of his own personal capacity. The basic prerequisites for every big man were his excellent rhetorical and organisational skills, together with his wealth and generosity. In the picture these prominent men are showing off their wealth, which in this case comprises sea-shells. They both are decorated with these shells that are formed as necklaces and they also hold their most precious jewels, i.e. large kina shells, in their hands . The photo was taken in 1937 by the Australian prospector Daniel Leahy, who noted that the procession of big men was watched by thousands of onlookers. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

Women took care of the majority of the field-work; they provided daily supply of plant foods for their male partners, their children and the family’s pigs. The males’ activities included hunting, fishing, tree-felling, the removal of unwanted vegetation from the fields and building fences. Both genders participated in the collection of non-domesticated plants, not only for as food but also for other purposes. Within the community itself the opinion of each member had its own weight, but there still existed the category of the “big men”, the ones who owned more gardens, more pigs and more stone axes. In practice, the power of big men was applied only in extreme cases of society-wide importance and in ritual activities. In most cases matters involving the daily routine did not mesh with their ambitions.

Soon agriculture in New Guinea came to be regarded as a good means of imaging the growing the crops in European prehistory. Agriculture involved with the cultivation of taro and yams can be dated to the period as early as 6950-6440 BC. This makes this area one of the major centres of the neolithisation process thereby permitting the use of local analogies for areas that are both remote in time and geographically. Although this is not a direct analogy, it is certainly as a primary plane of interpretive imagination.

The ownership of the land as such, although it was considered by the Bomagai-Angoiang as belonging to its clan, was in fact related only to the uncultivated territory. The gardens were owned by individual men, which was also true in regard to the abandoned land, whereas the preferential right to cultivate a crop belonged to the original owner. The gardens were separated from their surroundings by means of a strong wooden fence. The plots that were located in the landscape were in different stages in regard to the ripening of the crops and had differing fertile soil potential, depending on how the new gardens were established and which crops were planted on the old ones. In addition to the crops that were cultivated domesticated animals also contributed to the livelihood of the Bomagai-Angoiang, which in terms of their genera were restricted solely to pigs, dogs and chickens. Of the three, the pigs were by far the most important and this was not simply in terms of their contribution to subsistence as such, but also taking into account their overall impact on the native culture. Traditionally pigs were an attribute of wealth and a measure of the price involved in large-scale exchange transactions. These certainly included weddings at which the bride price was accounted for by the number of pigs.

|

|

| The percentage of individual species grown by Bomagai-Angoiang people. Yams clearly outnumber all the others. |

|

|

| A picture of the cultural landscape located in one of the many fertile valleys in the Highlands of New Guinea. Photo by Jan Rendek, the Dani, Western New Guinea (Papua), 2008. |

|

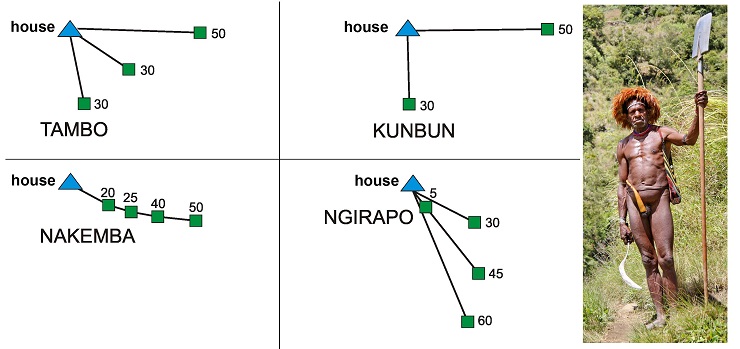

| Distance between dwellings (triangles) and gardens (squares) of four Bomagai-Angoiang men. Numbers indicate walking time in minutes. After Clarke 1971, 167. Photo by Jan Rendek, Dani, West New Guinea (Papua) 2008. |

|

| A specific activity, in which particularly women were engaged in the Highlands, was the production of salt. They dipped palm leaves into the salt spring, which they subsequently burned and the ashes were then wrapped in bundles of leaves. This commodity represented an attractive exchange article. Photo by Jan Rendek, Dani, Western New Guinea (Papua), 2008. |

Want to learn more?

- Brass, L. J. 1941. Stone Age Agriculture in New Guinea. Geographical Review 31 (4):555-569. doi:10.2307/210499.

- Blackwood, B. 1950. The Technology of a Modern Stone Age People in New Guinea. Occasional Papers on Technology 3. Oxford: University Press.

- Clarke, W. C. 1971. Place and people: an ecology of a New Guinean community. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- Cranstone, B. A. L. 1971. The Tifalmin: a “Neolithic” people in New Guinea. World Archaeology 3:132-142

- Fullagar, R., J. Field, T. Denham, and C. Lentfer. 2006. Early and mid Holocene tool-use and processing of taro (Colocasia esculenta), yam (Dioscorea sp.) and other plants at Kuk Swamp in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Journal of Archaeological Science 33:595-614.

- Healey, Ch. 1990. Maring Hunters And Traders. Production and Exchange in the Papua New Guinea Highlands. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rappaport, R. A. 1984. Pigs for the ancestors: ritual in the ecology of a New Guinea people. A new enlarged ed. New Haven: Yale University Press (1st published 1968).

- Souter, G. 1964. New Guinea: the last unknown. London: Angus and Robertson.

- Steensberg, A. 1980. New Guinea gardens. A study of husbandry with parallels in Prehistoric Europe. London: Academic Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)