The Wodaabe were called Bororo (which can be translated as “tattered herdsmen”) by their neighbours, who had settled in agricultural villages. The Wodaabe, however, considered themselves to be the most beautiful people on the planet. On a planet that cannot actually belong to anybody, because if any people did want to appropriate it, they would inevitably have to become the Shepherds of the Sun.

|

| A Fulani boy is leading a herd of cows that belong to his father. One day his son will be herding his own cattle. Photo by Viktor Černý, Niger, 2004. |

In 2001, approximately 100,000 of these pastoral nomads were registered. They constitute part of the largest nomadic population in the world who are defined as the Fulani ethnic group. They live scattered throughout the dry grassy strip of the vast African savannah running from both Senegal and Gambia in West Africa to the area where the former French Equatorial Africa was located to the east (which now comprises Chad, the Central African Republic, Gabon, the Congo and Cameroon). It is estimated that roughly between 25-40 million of the Fulani are living in Africa. In terms of their basic cultural characteristics it is important to know that historically they divided into a number of separate groups, amongst which it is generally possible to distinguish those who are nomadic herders, semi-sedentary agro-pastoral groups or simply agricultural settlers.

We will examine the proud herding Fulani, who combined their cultural identity with the spread of Islam in West Africa more closely. Through their extensive network of partners in exchange they were able to establish functioning long-distance trade routes throughout the region. The actual livelihood of indigenous herders, however, was always specifically associated with herds of cattle and sometimes also complemented by a smaller number of sheep, goats and/or camels. Both symbolically and in terms of subsistence the axis of the existence of every Fulani man was his herd. The amount of cattle owned represented both the wealth and the social standing of every man.

|

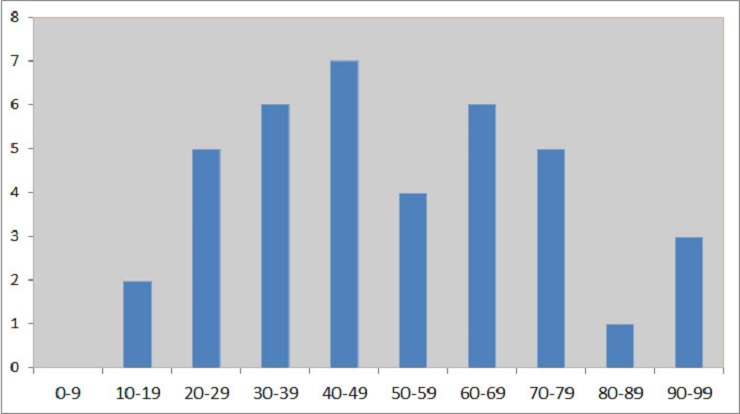

| Normally the size of the Fulani’s family herds ranged between 20 and 80 animals. Derrick Stenning recorded this evidence in the 1950’s in relation to the Fulani Wodaabe group. According to Stenning, 1959, 169. |

The movement of the pastoralist groups over greater distances depended on several factors, of which the climate played the primary role. During the dry season, both the people and thee herds moved south, where they dispersed. During the rainy season they returned back to the north to avoid the nuisance of the tsetse fly and the groups then concentrated again in larger units. Another factor was the amount of pasture that was available, which was influenced by the degree of concentration of the present herdsmen and their animals, the occurrence of cow disease and the accessibility of the agricultural markets. A completely different mode of pastoral migration prevailed in the geographically higher-lying areas, where the movement of herds was minimised and mostly restricted to the valleys that were passable.

The family and its mobile property constituted a basic social and economically independent unit. The livelihood of the family was always highly dependent on the prosperity of its herds, which meant that the Fulani sought for a steady increase in the number of their cows. With regard to this the cattle were only slaughtered for meat for ceremonial and ritual reasons. The sale of animals occurred only rarely. Effectively the herders needed to be able to pack all their other belongings, load them onto the back of donkeys or of oxen and transport them to another habitation. Dwelling on the road consisted of using simple shelters that were always constructed based on the same pattern. The homestead, however temporary it was, would always be divided into two halves - the back area was residential, while the front area served for technical purposes and for housing the livestock.

|

|

| The Fulani herders move their household together with their herds of cattle. They need to be able to pack all their other belongings, load them onto the back of donkeys or of oxen and transport them to another habitation. Photo by Viktor Černý, Niger, 2004. |

The Fulani households were intertwined by a kinship network of patrilineal clans. These were partially endogamous, because marriage between cousins was given preference. The clan, as such, had its own leader, who held his position based on his public election; the candidate, however, needed to have the proper origin, age and status. The clan leader represented his group externally in regard to dealings with other communities or with the state administration. On the Ancestral Board his authority, supported by his position and experience, carried a lot of weight. Therefore, when it came to determining the destination of next migration, the owners of the herds did listen to his advice. The land through which the Fulani and their cattle travelled was not a no-man’s land. Therefore, the herder leaders had to negotiate with the settlers concerning the use of their pastures or even for just passing through with their herds. To this end specific client relationships were created that were not based solely on profit, while their solid foundation was established based on the ritual aspect of traditional land management.

|

|

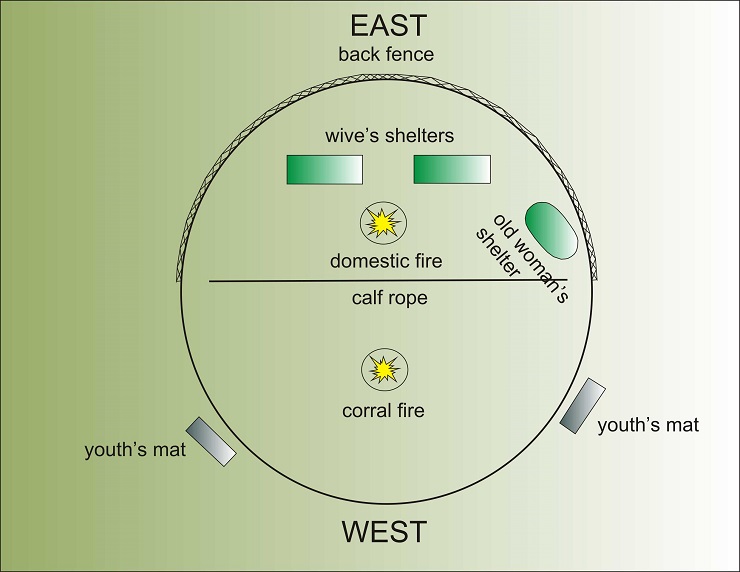

| A model plan of a Wodaabe camp settlement. The entrance is located on the west side, while the residential area is in the eastern half of the camp. According to Stenning, 1959, 106. |

|

| A Fulani household consists of a tent shelter for sleeping, a storage platform and an outdoor courtyard in which most of the domestic work activities take place. Photo by Viktor Černý, Chad 2003. |

|

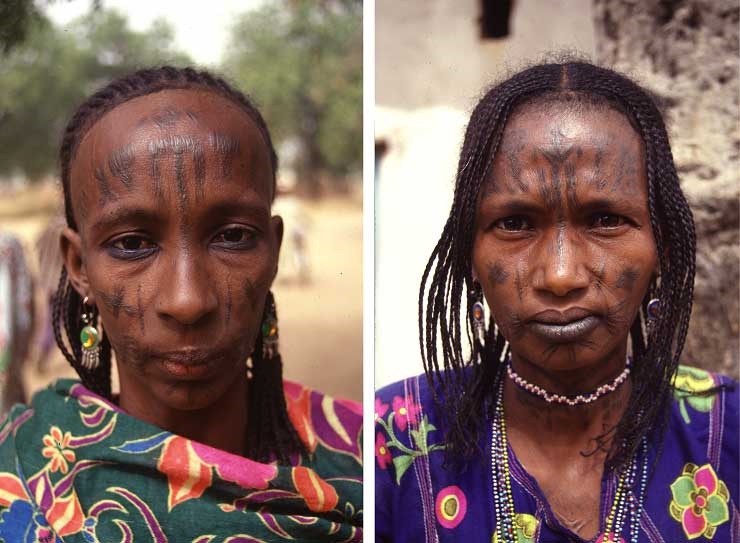

| The Fulani differ from the other African populations on the basis of their great emphasis on personal physical beauty. The faces of the two women in the picture are covered with traditional tattoos. Their black lips highlighted with henna also constitute a part of the native aesthetic code. Photo by Viktor Černý, Cameroon 2003. |

Want to learn more?

- Černy, V., L. Pereira, E. Musilová, M. Kujanová, A. Vašíková, P. Blasi, L. Garofalo et al. 2011. Genetic Structure of Pastoral and Farmer Populations in the African Sahel. Molecular biology and evolution 28 (9):2491–2500.

- Herzog, W. 1989. Herdsmen of the Sun. Movie. 52 minutes.

- Stenning, D. J. 1957. Transhumance, Migratory Drift, Migration; Patterns of Pastoral Fulani Nomadism. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 87 (1):57-73.

- Stenning, D. J. 1959. Savannah nomads: a study of the Wodaabe pastoral Fulani of Western Bornu Province Northern region, Nigeria. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)