In urban mythology Eskimos are defined as frost resistant natives who live alone in igloos, dress in furs, track polar bears on dogsleds and eat raw meat. Like every other cultural stereotype, this one does contain a grain of truth, as we will later demonstrate, while including a certain degree of criticism.

The climate of the entire Arctic region is primarily characterised by coldness, but also by its large range of seasonal variability. In the summer, which only lasts for six to twelve weeks, however, the temperatures do also reach above freezing and this is reflected in the flora that is present (lichens, mosses, shrubs, grasses...) and also the fauna (caribou, muskoxen, polar bears, foxes, rabbits, seals, walruses...). During the period of ever-increasing coldness from September onwards the sea freezes and with the exception of seals and walruses, all the other animals move south or ensconce themselves in hibernation. The temperatures drop well below -30 °C and very strong winds blow. This freezing weather continues until the end of July. Humans have been able to adapt even to such extreme conditions, however.

|

|

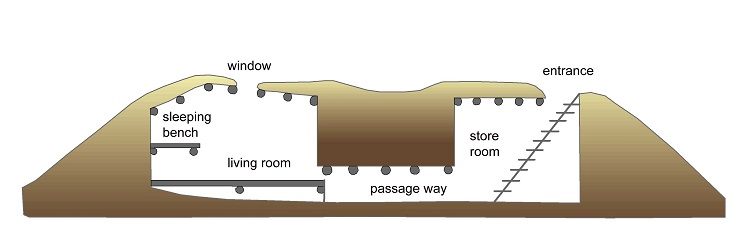

The cross section of a house inhabited by the Inupiat in the Cape Nome area in around 1879. |

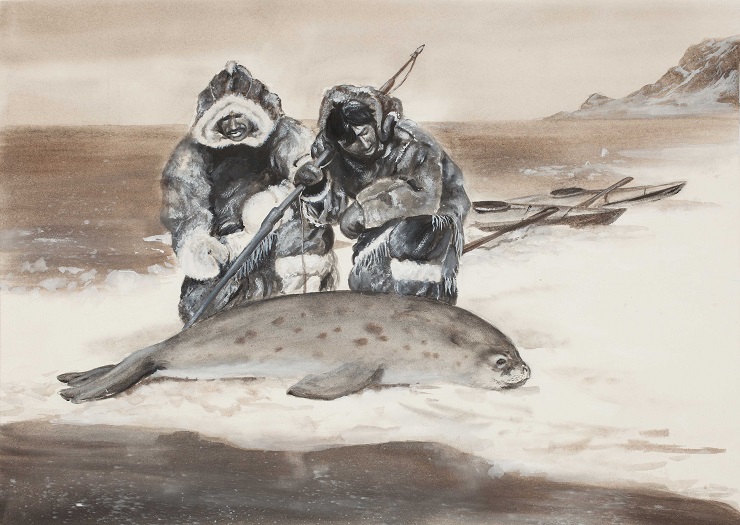

The freezing natural environment of the Inuit territory provided the base for the specific aspects of their cultural adaptation. Because of the cold, unlike in many other hunter-gatherer societies, the long-term livelihood in this locality was dependent on stockpiling edible resources by either drying or freezing them. The coldness demanded an entire series of specific inventions, e.g. the locals addressed the heat protection of the body by using the typical fur parkas, mitten gloves and thermally insulated soft snow-boots. They mastered travelling in a snow-covered landscape by using sleds pulled by domesticated dogs. Both in winter and in summer they had to move around in an environment in which the significant features included water obstacles that they overcame by utilising lightweight leather kayaks. Nordic hunters managed the hunting of such marine mammals as seals and whales with the help of a harpoon, i.e. a spear with a tip that becomes detached from the haft after hitting an animal and that the hunter holds on the attached rope.

In the Alaskan territory that was inhabited by the later Inupiat ethnic group it is possible to trace Palaearctic settlement as far back as 8000 BC especially in the localities in the interior, through which caribou migrated. The colonisation of the foreshore occurred much later – in around 1500 BC. During the period from 500 BC to 1000 AD significant links manifested in the material culture between the Arctic parts of Asia, the Island of St. Lawrence in the Bering Strait and Northern Alaska.

|

| All year round the Inuit had to move around in an environment in which the significant features included water obstacles that they overcame by utilising lightweight leather kayaks. Nordic hunters managed the hunting of such marine mammals as seals and whales with the help of a harpoon. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

At the time of the first contact with white men in the 19th Century the Inupiat population in Alaska accounted for cca. 10,000 people. Their settlement system varied depending on the specific geographical location of their community. For the greater part of year people stayed in one location in the aggregated residential units. The largest native Alaskan communities accounted for 400-600 people. These groups who settled in the northern coast of Alaska were able, during most of the year, to hunt whales, seals and walruses, and thereby there was no absence of subsistence that would force them to migrate. Local people were undertaking transfers over longer distances, however, primarily for trading purposes. On the west coast of Alaska, people lived in smaller winter settlements of 50-100 people, while in the course of the year they moved three or more times seeking a greater availability of food sources. At that time the Inupiat of the Alaskan interior were almost pure nomads, though they usually did not live in igloos and only built them as makeshift structures out of necessity.

Although the dwellings were diverse, they did have two elements in common – both had a partial recess and also an entrance via an underground tunnel. In summer the Inupiat moved out of their villages because their underground homes were flooded with water from the melting snow and so they set off on hunting expeditions.

The most important connecting link in regard to social relations amongst the Inuit was kinship. This solidarity reached an almost xenophobic level, whereby any foreigner was automatically considered to be an enemy who was destined for immediate liquidation. Based on this form of logic communities were formed of mutually related persons, descended from both sides of the family (i.e. both the father and the mother). The Inuit society had long been considered to be egalitarian, but there was always still a significant umialik person, the patron of most of the collective activities. The society was male-dominated and while the women carried out their household activities, the men were out hunting. This was also reflected in the high degree of preference for male offspring. On the other hand, men’s work was more dangerous, however. During the summer the Inuit hunted caribou for meat and for the needed skin, while in the winter they hunted seals and foxes. Hunting and fishing accounted for the bulk (90%) of their food supply and only a small percentage was obtained by gathering birds’ eggs, collecting clams and, in summer, picking wild fruits.

Want to learn more?

- Balikci, A. 1989. The Netsilik Eskimo. Long Grove: Waveland Press (1st ed. 1970).

- Goddard, I. 1984. Synonymy. In Handbook of the North American Indians (general editor W. C. Sturtevant). Vol. 5: Arctic, ed. D. Damas, 5-7. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Kemp, W. B. 1971. The Flow of Energy in a Hunting Society. Scientific American 224 (3):104-115.

- Langdon, S. J. 2002. The Native People of Alaska. Traditional Living in a Northern Land. Anchorage: Greatland Graphics.

- Plog, F., C. J. Jolly, and D. G. Bates. 1976. Anthropology: decisions, adaptation, and evolution. 1st ed. New York: Knopf: distributed by Random House.

- Stefansson, V. 1913. My life with the Eskimo. New York: Macmillan Company.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)